News Story

Resnik, Vaughn-Cooke interviewed about mental health tracking in Newsweek

You can now count your steps, measure your glucose levels, monitor your blood pressure and track your caloric intake from your phone or high-tech wristband. But for those dealing with depression rather than diabetes, or trying to keep tabs on their bipolar disorder rather than their weight, the pickings are slimmer.

There are apps that track mood by asking users to fill in surveys, ones that give tips on breathing or thinking positively, others that remind people to take their antidepressants or other medications and even some that turn cognitive treatment into games. The problem is that many lack a substantial basis in research, and the kind of information a user can provide can be severely limited. Another problem is that many patients are either not motivated or not self-aware enough to respond accurately, says Philip Resnik, a computational linguistics professor at the University of Maryland, who is studying how natural language processing can shed light on mental health.

Researchers are beginning to link to mental health certain types of data that people can’t track or identify in themselves. Just as an EKG is a more effective tool to diagnose cardiac disease than asking a patient how his or her heart feels, these new data sources could radically change our ability to track mental health.

Several recent projects have begun to explore ways technology can be further leveraged to address an increasingly dire situation in the U.S. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), one in four adults experiences some form of mental illness each year, while about 6 percent of the population is living with a serious mental illness such as schizophrenia, major depression or bipolar disorder. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 89.3 million people in the U.S. lack access to mental health care.

Technological tools to flag mental health problems could have a huge impact on these populations, which could use an easily downloadable app for early screening instead of jumping through hoops to find a qualified clinician just to start the process.

In addition, moving to tech could help better reach a younger generation. Roughly 20 percent of teenagers (ages 13 to 18) in the U.S. experience severe mental disorders each year, according to NAMI, while suicide is the third-leading cause of death for those ages 15 to 24. “A lot of psychology still takes place on paper,” says David C. Cooper, a Mobile Health Program psychologist at the National Center for Telehealth and Technology (T2), which leads initiatives for the Department of Defense that use technology to deliver psychological health care options to the military community. He was referring to traditional therapy tools like the paper journal he asks patients to keep between sessions, and the notes he takes during those meetings. With 70 percent of military personnel under the age of 30, the generation of veterans Cooper treats is starting to expect tech as part of their treatment.

“If I give patients a piece of paper, they’re going to look at me like I’m some sort of Luddite,” Cooper tells Newsweek.

Cooper has helped develop apps like PTSD Coach, Mood Tracker, Breathe to Relax and Virtual Hope Box that translate standard, analog mental health care practices into ones and zeros. But using new kinds of data and technological capabilities to track mental health is a daunting task. Unlike measuring glucose levels, which can easily help patients (and their doctors) understand where they stand, there is no direct way to measure depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or PTSD.

Carol Espy-Wilson, a professor of computer and electrical engineering at the University of Maryland, is working with Monifa Vaughn-Cooke in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, and Resnik, the computational linguist, to come up with a complete set of measures—physiological markers like heart rate and skin temperature, along with patterns based on vocal features, facial expressions and language use—that could help track mental health.

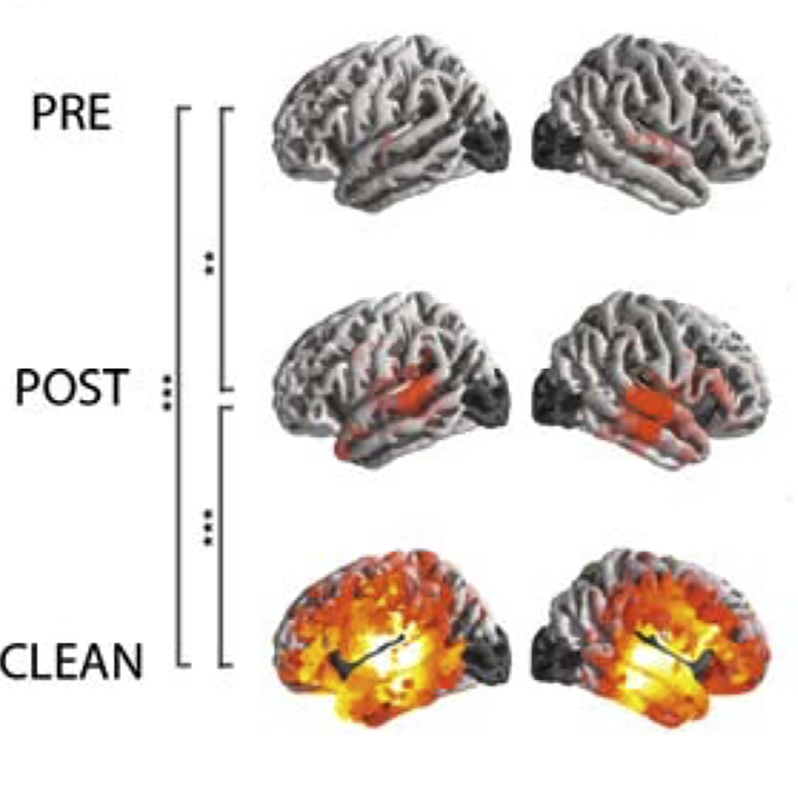

Espy-Wilson started by looking at the Mundt database, collected in a study from 2007 that looked at depression and speech patterns. The Mundt study recorded participants, all of whom were undergoing treatment for depression, as they spoke freely and assessed their depression on the standard Hamilton Depression Scale.

Espy-Wilson’s study built on those findings. She looked in particular at six patients whose assessments showed the greatest variation in mental well-being week to week. She found that when they were depressed, their speech tended to be slower and their vowels “breathier,” and that their voices’ “jitter and shimmer”—a measure of variability in duration and amplitude of sound—increased.

Meanwhile, Vaughn-Cooke is running a study with healthy participants, which she’ll later repeat with others who have been diagnosed with depression, prompting them with questions like “How was your day?” and “What was the saddest part of your day?” The responses are recorded with both video and audio. The former will be analyzed for emotion using facial recognition software, while the latter will be sifted through to identify vocal patterns as well as transcribed and analyzed as text.

That’s where Resnik will come in. He has already been looking for “signals in language use that help produce insight into people’s mental health status,” he tells Newsweek. In other words, his goal is to connect speech or writing, whether it’s an essay or a tweet, to something that can identify problems with a person’s mental health—something like the Hamilton Depression Scale, for example.

“Once [we start] understanding how all of these different predictors relate to each other, we can then develop algorithms to better predict when a depression patient is going into a relapse,” Vaughn-Cooke says. This will “not only improve quality of life but also reduce incidence of suicide, relapse and readmission to treatment facility.”

Ideally, all this will be streamlined into one app that would collect this information while a person is going about his day, potentially asking him to record responses to questions periodically in addition to continuous passive tracking. The result will be a tool, a Siri on steroids, that can track mental health outside of formal treatment or between therapy sessions. “You want people to get the kind of attention they need when they need it,” says Espy-Wilson.

Glen Coppersmith, a research scientist at Johns Hopkins University’s Human Language Technology Center of Excellence, has been studying Twitter in an effort to understand just that. His work focuses on quantifying signals—whether from the text itself or from the tweets’ metadata (e.g., the time and location of tweets and degree of interaction)—that are relevant to mental health and could potentially lead to intervention. He and his colleagues have already figured out how to parse people’s Twitter feeds and identify whether they’ve been diagnosed with depression, bipolar disorder, PTSD or seasonal affective disorder.

In early November, Coppersmith will run a weekend-long hackathon at Johns Hopkins. A few dozen attendees—computer scientists, statisticians, psychologists and others—will work in groups on a data set from Twitter, trying to learn more about subtle cues and patterns that could cumulatively indicate something about users’ mental health.

Some efforts have already made use of social media to track mental health. The Durkheim Project, run by a team from Dartmouth University and the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, launched in July of last year. The goal of the project is to analyze data from the social media accounts and mobile phones of veterans who opted in to try to find ways to predict suicide risk. Until recently, “most of the available signals about mental health state through language were not accessible—[like] the conversation by the watercooler at work or at the dinner table at home,” says Resnik.

But now that many of our interactions happen in public forums, like Twitter, “we’re starting to have data that’s relevant that we can derive insights from, that we can build technology on,” says Coppersmith.

One company, Ginger.io, has released an app that uses phone sensors to track mental health in patients who are participating at the suggestion of one of their health care providers. The app is built on the hypothesis that the ways people use their phones can provide important information about mental health. It runs in the background and builds a model of its owner’s behavior patterns.

It can then “notice” and flag any behavioral patterns identified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as potential markers of depression. An increase in missed calls or texts, for example, could indicate reduced social interaction. Changes in sleep cycles often accompany depression and bipolar disorder, so the app uses sensors and activity to track sleep. GPS and other movement-tracking sensors can be analyzed for patterns that might indicate lethargy.

“None are perfect diagnostics,” says co-founder and CEO Anmol Madan, but when risk factors are picked up by the app, it can “send them a message, coaching, a question or set up interaction with a nurse or provider.” It’s a “first level of triage,” he says, but the intervention, communication and support patients need is still done by people, psychologists and other mental health professionals.

Closing the circuit between the technology and the professionals and larger health care system is part of the challenge, Stacie Vilendrer, an M.D./MBA candidate at Stanford University who has studied ways to harness technology to benefit patients, tells Newsweek. Beyond the difficulty of asking longtime clinicians to change their ways, there are concerns about patient privacy and the potential for liability. “For example, if an app collects information that a patient is suicidal, dumps this information into a portal that the physician has access to, and the patient commits suicide without any physician intervention, it would seem the physician is still liable,” Vilendrer says.

It can also be a disheartening challenge for researchers and entrepreneurs to find ways to work within the U.S.’s complicated health care system, she tells Newsweek.

But “mental health is something that has touched every single one of us at some point in our lives,” whether it’s a personal experience or watching family or friends go through it, says Coppersmith, who predicts that a spike in research activity around technology and mental health is coming. “I don’t know how you can’t attack this problem. This is the one everyone should care about.”

November 12, 2014

Story by: Stav Ziv

Published November 12, 2014