News Story

Arthur Popper talks about the not-so-silent world of the ocean

In 1956, the French adventurer and SCUBA inventor Jacques Cousteau published a book called The Silent World about Earth’s oceans. Cousteau’s book is widely credited with giving rise to a new awareness of the seas’ beauty and fragility.

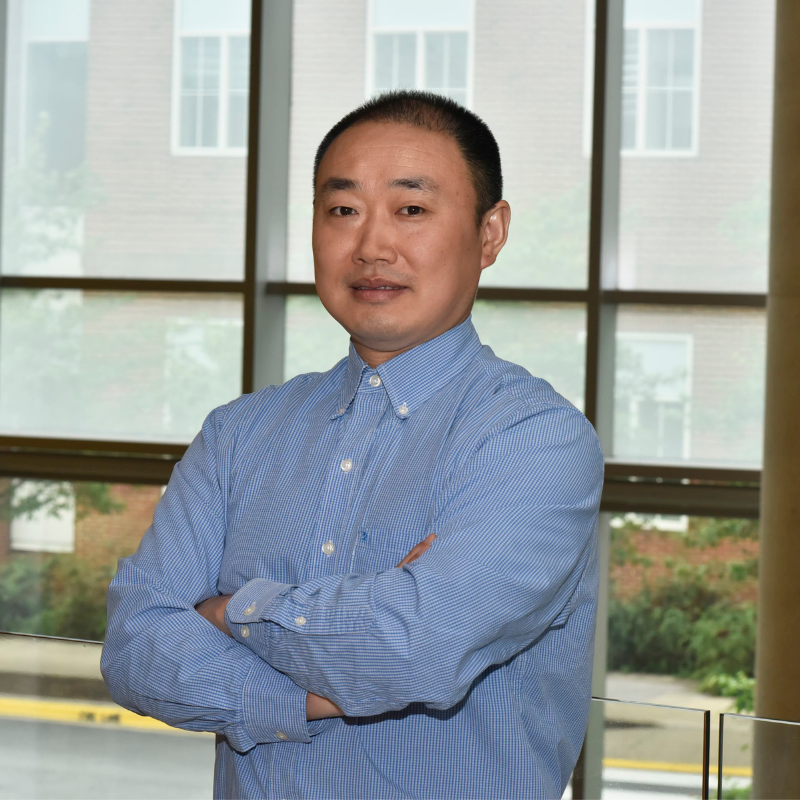

"He picked a bad title," said Arthur Popper, professor emeritus in biology at the University of Maryland in College Park. The oceans are not silent. In fact, they are louder than ever. And that, scientists believe, is a problem.

The creatures that dwell in the ocean make noises to communicate, find food and locate themselves in their world. The oceans are naturally so noisy that sonar operators in World War II often confused the sounds made by whales with noises from German U-boats.

Like humans, aquatic animals learn to adapt to natural noises, such as the sounds of other animals, wind, surf and waves, said Popper. They evolved hearing as a way of forming an “auditory scene,” a way of observing things not within your sight, like a predator sneaking up behind them. You can’t very well see in the oceans, after all.

Today, however, much of the world's underwater sound is human-made (“anthropogenic”), the result of shipping, fishing, exploring for resources, construction and military operations. The amount of this anthropogenic sound is increasing.

“It’s only after you add the cacophony of sound we add that you start to think it could have an adverse effect on them,” he said.

But aside from a few well-studied species, how the creatures of the ocean are affected by this noise is largely unknown.

Several years ago, the impact of military sonar on marine mammals was extremely controversial, with several incidents of beached animals, particularly beaked whales, attributed to sonar. Federal courts ruled the Navy had to mitigate the noises it was making.

Despite the publicity, mostly generated by environmental groups, the effect of military noise on whales may be not the biggest acoustic problem in the oceans, said Popper. For one thing, the vast majority of biological creatures in the seas are not marine mammals but fish and invertebrates. Less research has been done on them than on whales and dolphins because “they are not as cute as Flipper,” he said.

In the case of some animals, scientists don’t even know how their hearing works.

“The issue is non-trivial,” said Ted Cranford, adjunct assistant professor at San Diego State University, an expert on the physiology and anatomy of whales and dolphins. “Some organisms, like the baleen whales, we don’t even know how they hear sounds.”

Baleen whales, like the blue and fin whales, are the largest animals ever to live on Earth. They use a filter system called “baleen” to extract fish and invertebrates from seawater when they take huge gulps while feeding. Whales use sound to communicate, and because of the way sound travels through water, it can be a spectacularly efficient form of communication.

In the case of right whales, for instance, Christopher Clark, a bioacoustics researcher at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, has recorded sounds in the Bahamas made by endangered North Atlantic right whales off Cape Cod, 1,200 miles away. He has shown that anthropogenic noise can interfere with whales’ ability to hear each other.

The sounds all baleen whales make tend to be low-frequency, around 20 hertz, which in water equates to a wavelength of 75 meters (246 feet). But the fin whale, for instance, has a body that is only 25 meters long (82 feet), a third the size of the sound wave. Furthermore, it has relatively small ears.

“How in the world do they hear the sound?” said Cranford.

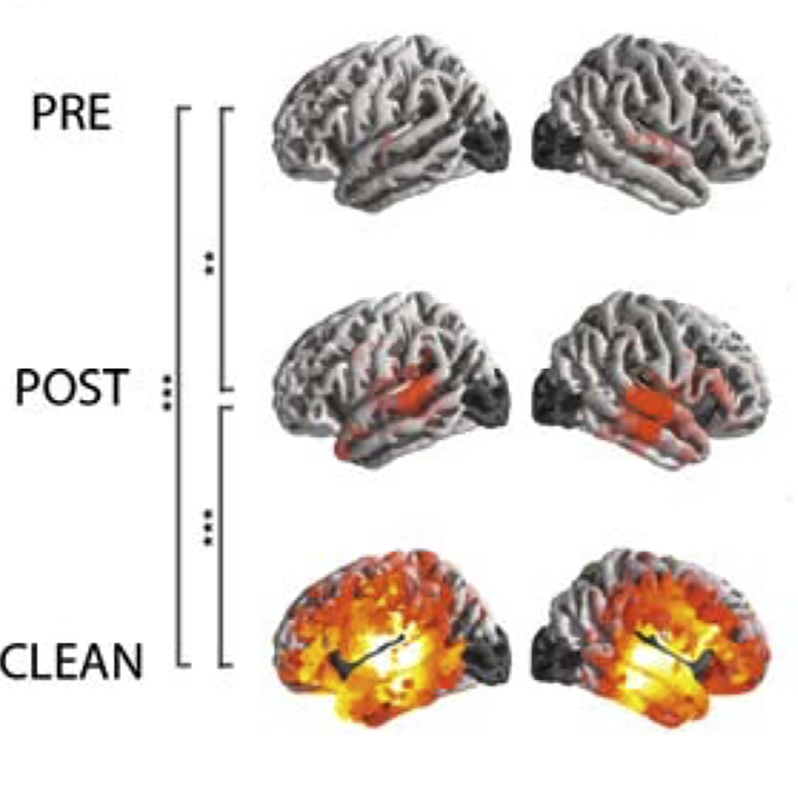

Cranford and his colleague Petr Krysl discovered that the entire skull of a fin whale vibrates in response to these low-frequency sounds and transmits the vibrations to the ears, which then sends them to the brain. Whales also get some sound from vibrations in their soft tissue. Since other baleen whales have geometries similar to that of the right whale, the probability is that all baleen whales hear that way.

Cranford points out that most of the sounds humans put into the ocean are low-frequency and may interfere with this communication.

Dolphins use high-frequency sounds for communication and echolocation, a kind of sonar that places them in their world and helps them locate food. Researchers at the Long Marine Laboratory at the University of California, Santa Cruz have discovered that dolphins shout when there is too much noise, which may have a higher metabolic rate, expending energy and using more oxygen.

Figuring out how fish respond to noise is even more difficult. There are about 32,000 species of fish, each with unique physiological characteristics. Each may react to different sound in different ways, from small random changes in blood pressure to death. If an introduced sound masks the natural sound, a fish might not know it is in danger.

Some fish hear better than others. Tuna and salmon hear poorly and may be less affected by loud noises. Goldfish and catfish hear better and might be more susceptible.

"Fish will ignore some sounds, but scientists know very little about which motivation may be a factor,” said Popper. Two fish mating might ignore a sound that would scatter them if they were not distracted.

There is no evidence they change migration patterns because of noise, he said. It is part of a long list of things scientists don’t know about noisy oceans.

September 11, 2015

Story by: Joel Shurkin, Inside Science News

Published September 15, 2015