News Story

The Mystery of Our Early Missing Memories

You can probably recall hazy visions of your preschool antics, but try to remember your second birthday, and you’re likely to draw a blank—or even conjure images based on party photos you saw years later.

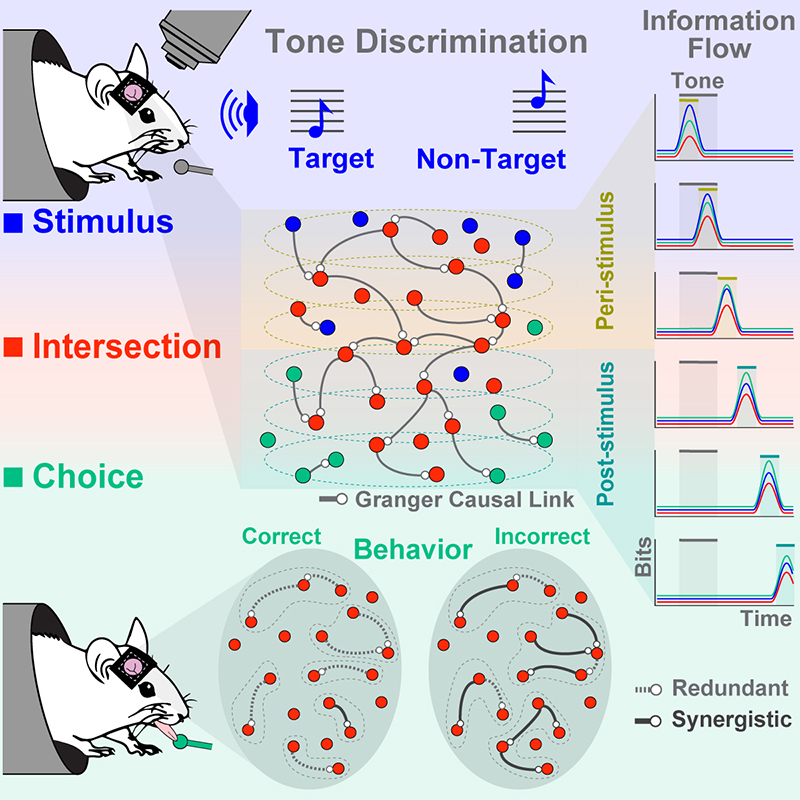

Researchers have long wondered what happens during early childhood to “stabilize” memories so that they are better able to stand the test of time, unlike those from our earliest years. Does the brain mature and then memory improves, or does memory improve, which then changes the brain? The answer appears to be both, according to a study led by University of Maryland psychology researchers published today in the Journal of Neuroscience.

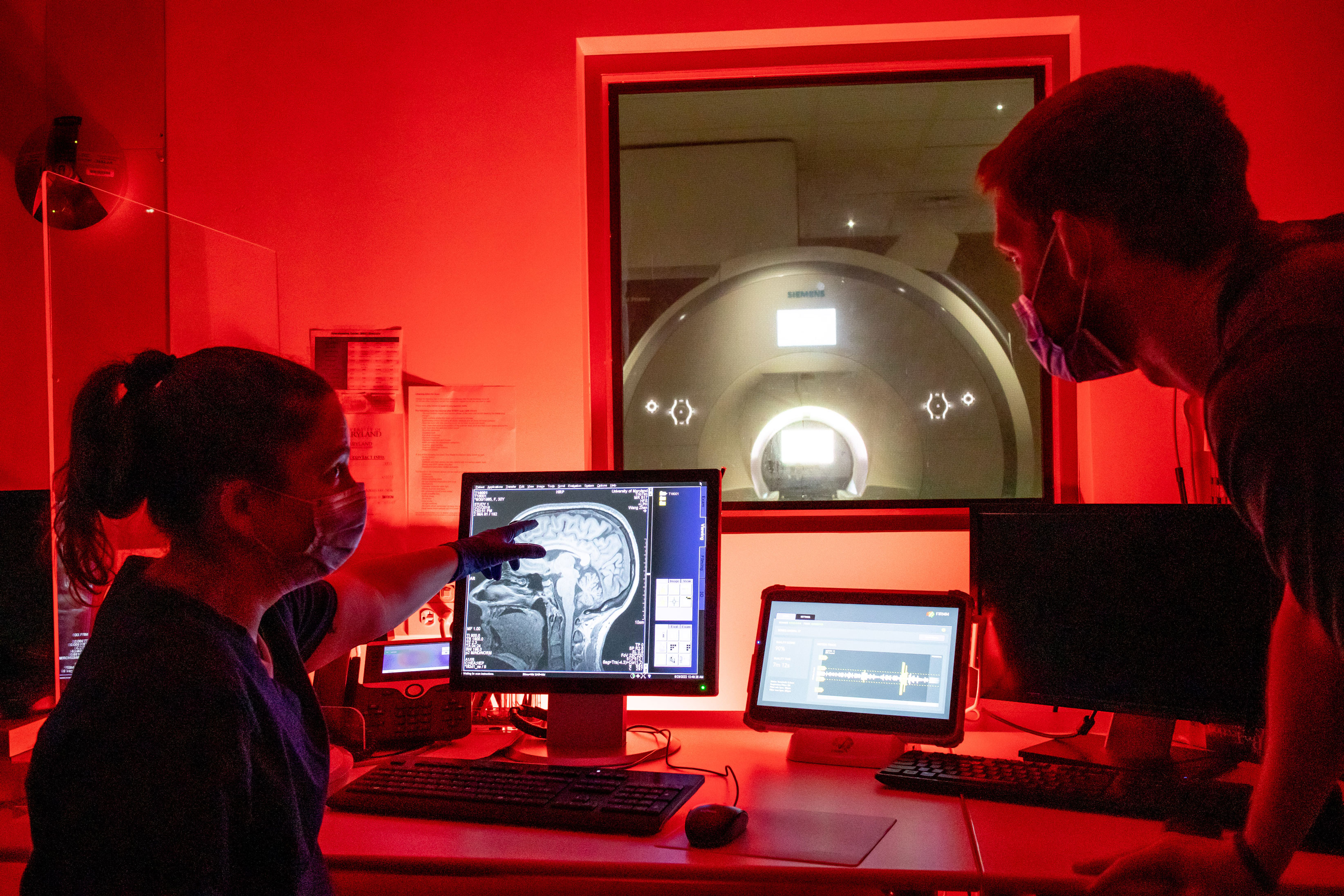

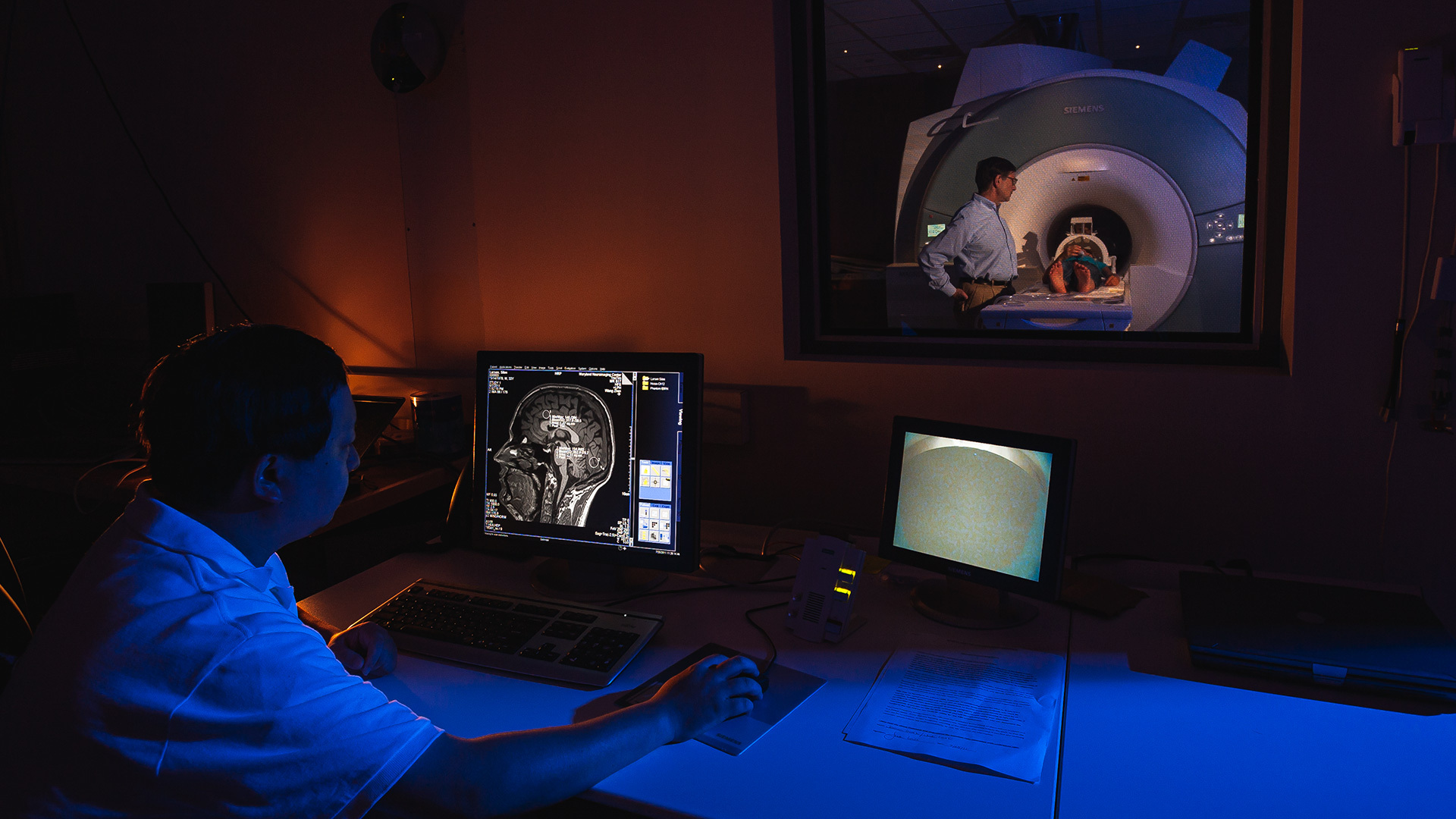

Researchers measured memory skills and resting brain activity in 200 children ages 4 and 6 over the course of three years. The children learned facts and were quizzed at intervals on the facts themselves as well as the process of learning them—from a specific character, for instance—with both factors working together to create what researchers call a “source memory.” Children also underwent yearly fMRI brain scans at the Maryland Neuroimaging Center on campus so that researchers could examine changes in connectivity known to be associated with memory.

“We discovered that changes in our ability to remember past events impact the brain and, conversely, the brain impacts subsequent changes in memory,” said UMD Associate Professor Tracy Riggins, one of the study’s lead authors. “These findings suggest that behavior and brain development are interactive, bidirectional processes, revealing that experience shapes future changes in the brain and the brain shapes future changes in behavior.”

Researchers also found that both timing and location in the brain matter where memory is concerned. Early changes in memory ability had greater impact on the brain than later changes; and some regions of the brain were more influenced by early changes in memory, while others were more associated with later memory changes.

“Together, these results highlight the intricate and reciprocal relationship between brain and behavior across development,” Riggins said. “Neuroimaging studies in young children are rare, as are studies that follow children as they grow from year to year, but this is the type of research required in order to explain how memory changes the brain and how the brain changes memory in early childhood.”

In addition to age-related changes, researchers also observed large differences between individual children, in terms of both memory and brain development. For example, some 4-year-old children have very good memories and strong brain connections, whereas others have poor memory abilities and weaker brain connections.

In the next phase of their work, funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, researchers plan to investigate the potential reasons for these differences between young children of the same age, for example, sleep patterns.

Fengji Geng from Zhejiang University and Morgan Botdorf, a Ph.D. psychology student at UMD, were also co-authors on the Neuroscience paper.

Original story by Sara Gavin, used with permission from the College of Behavioral and Social Sciences website.

Published December 21, 2020