News Story

Wearable Tech and Brain Imaging Innovate Treatments for Paranoia

High-definition videos of racially diverse, dynamic emotional faces—welcoming, neutral and threatening—are one way that the paranoia project improves upon traditional brain imaging. Video stills from Shutterstock.

A smartphone vibrates in a subject’s pocket. The notification asks a simple question: “How are you feeling right now?” But the message isn’t from a clingy friend or pushy relative.

The subject is participating in a UMD study that uses innovative tools, including smartphone-based digital phenotyping and wearable sleep monitoring devices, to inform the development of better treatments for extreme paranoia.

In casual everyday language, “paranoia” is often used to describe a mild feeling of social anxiety, but its clinical definition is more precise. Paranoia is the mistaken belief that intentional harm is likely to occur, and it spans a range of intensities, from low-level paranoid ideation to profound delusions—that is, from mildly uncomfortable uncertainty about other’s intentions to an unshakable conviction that one is being persecuted by government agents.

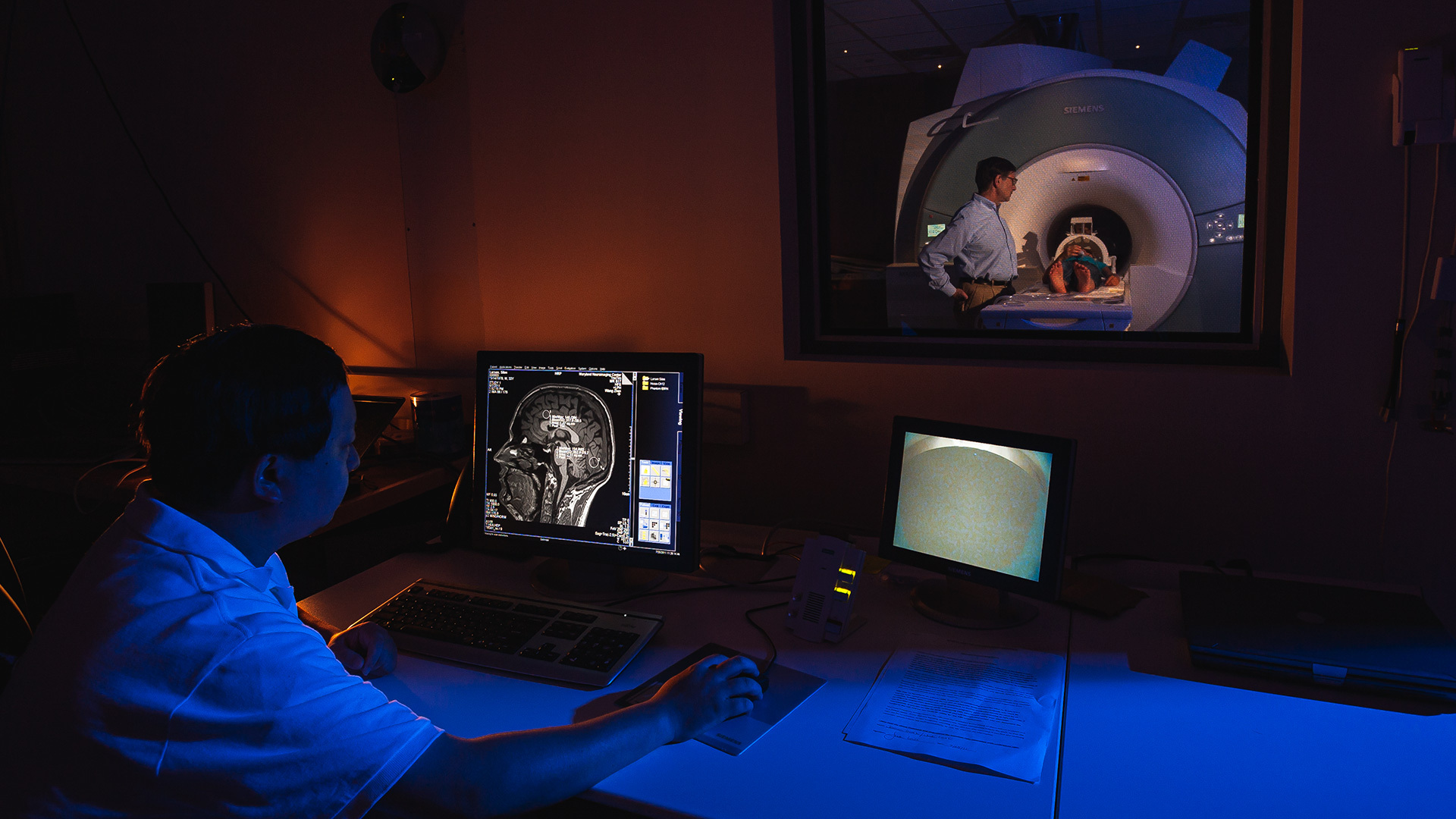

The UMD study correlates data about momentary experience gathered via wearable technology with brain scan data from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to better understand the nature and neurobiological building blocks of paranoia and the environmental contexts in which it flourishes.

Led by Associate Provost and Professor Jack J. Blanchard, Associate Professor Alex Shackman and Assistant Research Scientist Jason Smith—all in the Department of Psychology—the project was awarded a $3.7 million grant over five years from the National Institutes for Mental Health in 2021. In 2018, seed grant funding from the Brain and Behavior Institute (BBI) allowed the team, which also included Eun Kyoung Choe, Associate Professor at the College of Information Studies, to gather preliminary data and lay the groundwork for proposal submission and subsequent award.

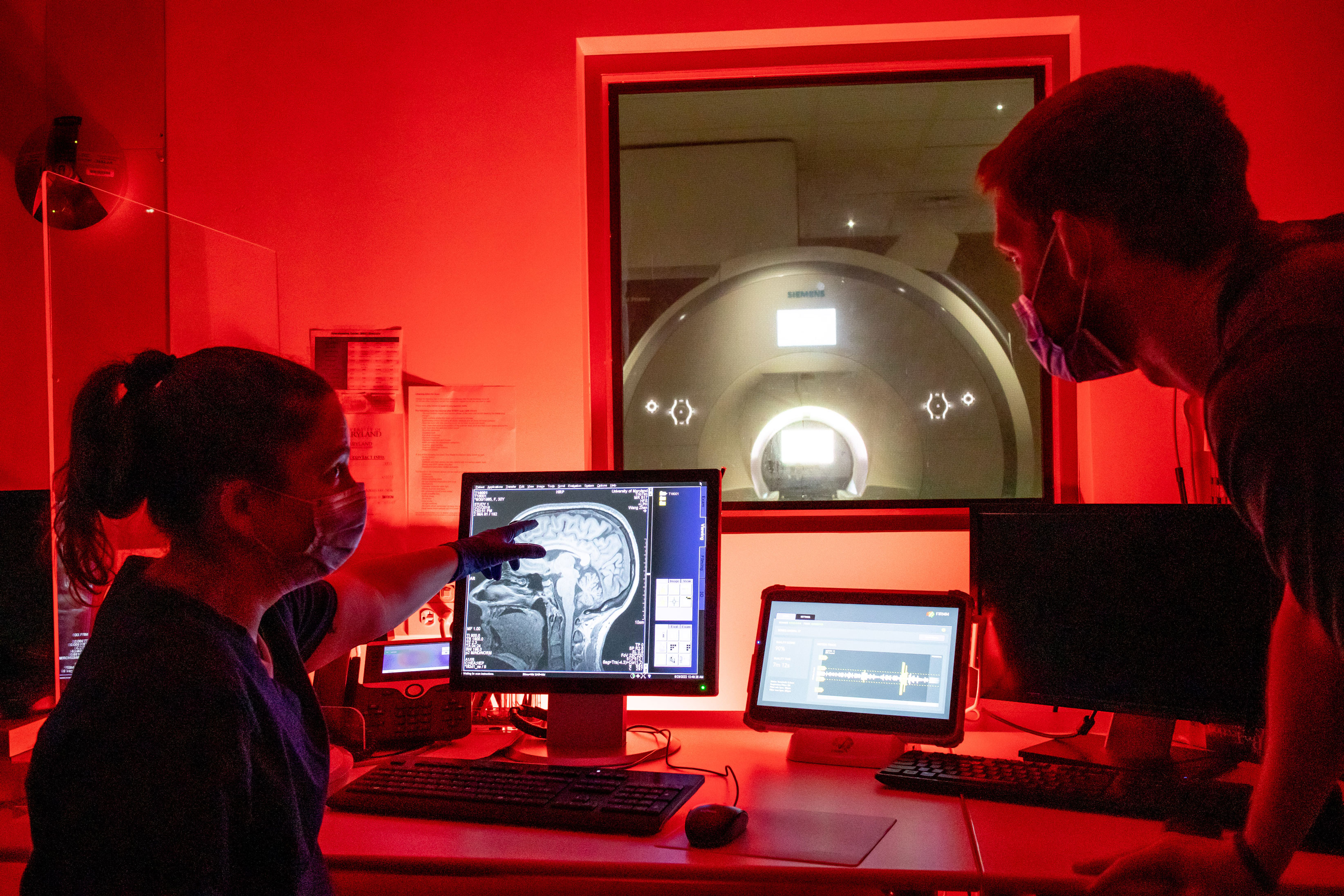

“Traditional fMRI brain scans make use of procedures that are well-controlled but highly artificial,” said Shackman. “They require a subject to lie absolutely still in a small dark tube while being bombarded by loud noises. How natural is that? This project will provide a crucial first opportunity to link brain circuit function, quantified in the artificial confines of the MRI scanner, to smartphone and wearable measures of everyday experience, behavior and the environment.”

The UMD team first devised an innovative collection of fMRI tasks that are more lifelike, dynamic and immersive than the norm. These tasks feature a battery of high-definition videos, including a suspense-filled Alfred Hitchcock whodunit thriller, bodycam footage recorded while walking on crowded sidewalks in London and Manhattan, amateur cellphone and security camera footage of chilling scenes (accidents, explosions, bodily assaults, casually walking along the ledge of a skyscraper), and close-up footage of racially diverse actors displaying a range of emotional expressions, from welcoming smiles and crinkled eyes to threatening gestures and aggressive shouts.

To improve measurements of paranoia as it ebbs and flows in real-world contexts, the investigators turned to wearable technologies. A smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment (EMA) tool allowed the researchers to overcome an important limitation of traditional assessments, such as questionnaires or diagnostic interviews—namely, the subject’s memory. With traditional approaches, subjects often have difficulty recalling important elements of their personal experiences. Smartphone EMA addresses this bias by contacting subjects up to eight times per day for at least a week to better capture how paranoia responds to moment-by-moment fluctuations in the social and physical environment.

The smartphone surveys are complemented by passive datastreams that unobtrusively track participants’ physical location and activity. Detailed geolocation maps can be cross-referenced against census bureau data, crime statistics and measures of neighborhood deprivation to determine the amount of chaos or threat in a particular location. The team can then quantify associations between where a subject is, how they feel, and how they react to momentary particular events, from traveling on a public bus to making a purchase in an unfamiliar store. This novel combination of data from EMA, community statistics and geolocation has the potential to identify the everyday factors that promote upticks in momentary paranoia.

For Blanchard and Shackman, one of the most exciting elements of the project is the introduction of a wrist-worn sleep actigraphy device to objectively monitor sleep-wake data and determine whether sleep problems increase the intensity or likelihood of paranoid thoughts and feelings.

“Insights based on sleep are much more clinically actionable,” explained Shackman. “Devising new treatments generally takes a lot of time and money, but there is already plenty of good infrastructure for treating sleep, such as therapists and sleep centers. If poor sleep quality turns out to be a key trigger, we could repurpose these resources to help people suffering from debilitating levels of paranoia.”

For a grand challenge like understanding the root causes of paranoia and other mental illnesses, actionable hypotheses and targets are vital.

“Psychiatric disorders, including extreme paranoia, impact many millions of people across the world,” noted Shackman. “The US has an opportunity become a real leader in developing new insights into the mechanisms that give rise to those illnesses.”

“We should address this challenge through the brain, of course, with animal models and other mechanistic approaches. But we can also approach it through the second ‘B’ in ‘BBI’—that is, through behavior. The smartphone digital phenotyping and sleep tracking tools promise to provide the kinds of information necessary to guide the development of more immediately actionable and effective behavioral treatments for individuals suffering from extreme levels of paranoia.”

###

Writer: Nathaniel Underland, underlan@umd.edu

About the Brain and Behavior Institute: The mission of the BBI is to maximize existing strengths in neuroscience research, education and training at the University of Maryland and to elevate campus neuroscience through innovative, multidisciplinary approaches that expand our research portfolio, develop novel tools and approaches and advance the translation of basic science. A centralized community of neuroscientists, engineers, computer scientists, mathematicians, physical scientists, cognitive scientists and humanities scholars, the BBI looks to solve some of the most pressing problems related to nervous system function and disease.

Published June 5, 2022