News Story

Alumna wins MacArthur 'genius' grant

Beth Stevens, Assistant Professor of Neurology at Children’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, Friday, September 18, 2015. Photo courtesy of John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

That sounds like the plot of a zombie plague movie, but it’s real, and mostly a good thing. About 10 percent of the brain is made of cells called microglia that scientists have long known are a vital part of the brain’s immunological defenses, rooting out damaged cells and infection and controlling inflammation.

They didn’t know about another crucial function of microglia, however, until Beth Stevens Ph.D. ’03—a graduate of the Program in Neuroscience and Cognitive Sciences—discovered it.

Stevens, now an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and the F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, found that microglia aren’t just a cleanup crew, but—thanks to their appetite for the brain’s underused wiring—play an important role in shaping its development. And when microglia malfunction, they may help cause a host of brain disorders.

The breakthrough resulted in Stevens in September being named a MacArthur Foundation fellow and receiving a no-strings-attached $625,000 “genius” grant. She says her lab can use this money to dig into fundamental questions about brain function without worrying about how to shape the research to attract grants.

“It allows you to focus on projects in areas of science that you’re really excited about that might otherwise not be tackled so quickly because they’re higher-risk projects, or ideas at the very early stages—mostly just scribbles on a whiteboard,” she says. “The MacArthur is really enabling, because it allows such flexibility and freedom to explore. It’s everyone’s dream as a scientist to be able to do that.”

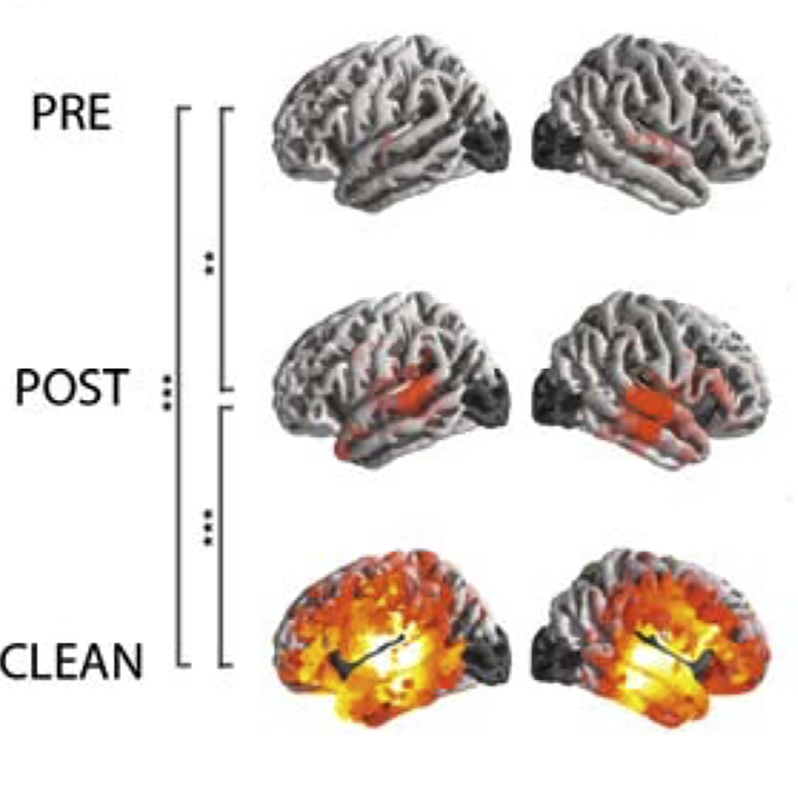

Stevens found in 2012 that in addition to their immune function, microglia also “prune” synapses—the electrical connections between brain cells that allow the brain to work—by literally eating them during brain development, a process that’s most active early in life. Microglia do this when they find protein molecules called “complement” bound to the synapses.

“Microglia recognize these as ‘eat me’ cues that say that these are the synapses that need to go,” she says.

That’s exactly how it should work in healthy brains, which initially are overstocked with neural connections, Stevens says. Microglia winnow synapses down to create a brain that’s more efficient and specifically shaped for the tasks it engages in.

“The most simple way of thinking about it is the idea of ‘use it or lose it,’ ” she says. “We all start off with extra connections that are kind of weak, and it’s like a rough wiring diagram. What’s really amazing is that the world you live in and the experiences you have start to refine and remodel that circuitry.”

When things go wrong, however, microglia might begin munching on connections they shouldn’t, damaging the brain irreparably. The bad kind of synapse pruning may be associated with autism and Alzheimer’s disease, for instance. On the other hand, too little pruning causes what Stevens calls a “hyper-wired” brain, and might be a cause of epilepsy.

Now she’s focusing on figuring out exactly what prompts complement molecules to attach to specific synapses, as well as the mechanism that allows microglia to notice and eat them.

Another key question—why do microglia go out of control later in life and begin chewing up needed brain cells?

“We’re really working hard in the lab to determine what regulates this pathway, and discover what causes microglia to become more phagocytic—to eat more,” she says. “Is this the exact pathway that happens during development that’s being reactivated? If so, why?”

Stevens has always been motivated to unravel the mysteries of brain function, but says recent breakthroughs—and the MacArthur Foundation grant—have her thinking more about how her discoveries can be used to develop drugs improve the lives of people with neurological disorders.

“This is long-term,” she says. “But this award has also kind of put that on the fast track.”

--Chris Carroll, TERP magazine

Published October 27, 2015