News Story

Michele Gelfand identifies useful negotiation strategies for 'Honor Cultures'

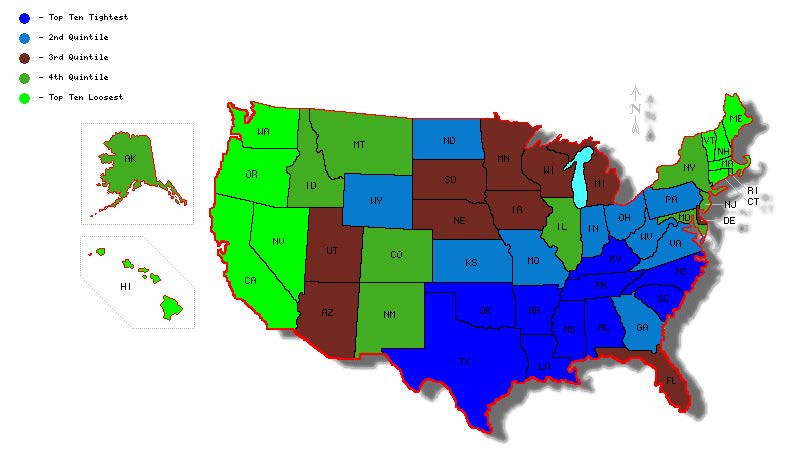

COLLEGE PARK, Md. – A new study led by the University of Maryland shows that Western diplomatic strategies based on rationality may backfire when applied to discussions with “honor cultures,” such as in the Middle East, African and Latin America. The authors of the study recommend that diplomats better tailor their word choice to the values of the culture with whom they are negotiating. Another outcome of the study is a new “honor dictionary” based on hundreds of interviews in the Middle East that identifies “honor talk” in negotiations and contrasts it with other dictionaries developed in the United States to assess more “rational talk.”

The study examines the role of honor in negotiations and was designed to complement the “rational” Western model of dialogue and to better serve honor cultures. The new proposed honor model—based on models found in many Arabic-speaking populations—illustrates the linguistic processes that facilitate creativity in negotiation agreements in the United States and Egypt.

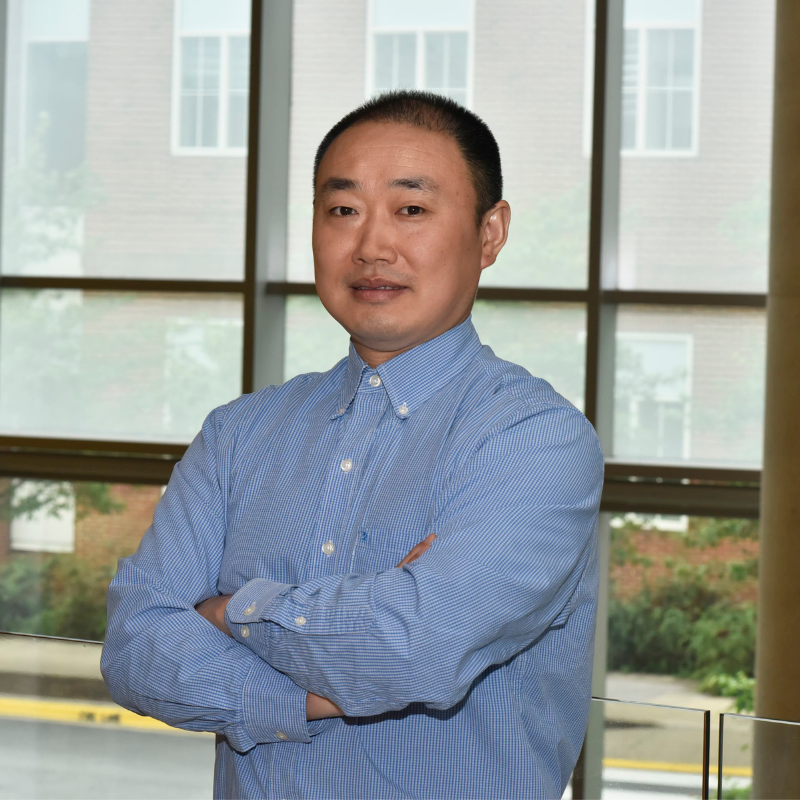

Led by Professor Michele J. Gelfand of the University of Maryland, researchers at UMD and the Egyptian Training Center Research in Cairo, Egypt, published “Culture and getting to yes: The linguistic signature of creative agreements in the United States and Egypt” in the Journal of Organizational Behavior. Gelfand is a part of UMD's Brain and Behavior Initiative.

In some cultures, maintaining personal honor is deemed more important than other benefits that might be gained in a negotiation, including goods or services. In these contexts, the Western model of seeking rationality and more objective measures of gain could be interpreted as being inhumane or counterproductive.

To examine how honor concerns play out in negotiation with Western cultures, the research team connected same-culture pairs of participants in the United States and in Egypt recruited from the community, who were given one hour to engage in a negotiation simulation. The simulation concerned a real estate developer that planned to open a mall and a large retailer that was interested in opening an anchor store in the mall. The situation gave negotiators opportunities to reach creative solutions by meeting each other’s underlying interests.

“We found that the same language that predicts integrative agreements in the United States—essentially, that which is rational and logical—actually hinders agreements in Egypt,” Gelfand said. “Creativity in Egypt, by contrast, reflects an honor model of negotiating with language that promotes ‘honor gain,’ or moral integrity, and ‘honor protection,’ or image and strength.”

When examining documents to build the new honor dictionary, the researchers found that U.S. negotiators used more words related to logical and reason—such as “analyze,” “idea,” and “think”—than their Egyptian counterparts. Egyptian negotiators used more words connected with the concept of honor, including “help,” “trust,” and “agree.”

“It’s interesting to note that the same rational language that predicts ‘win-win’ outcomes in the United States undermines agreements in honor cultures. For example, we found that Egyptians were more effective at reaching satisfactory deals the more honor language they used,” Gelfand said.

The researchers hope their findings can be applied to negotiations and dialogue between cultures around the world, at the personal, community, corporate and international political levels.

Published June 15, 2015