News Story

A New Nap-time Theory

How much young children need for naps—time their brain does the hard work of filing away new memories and experiences—is less dependent on age than how their brains function, new UMD research shows.

Many parents find themselves asking: Why do some young children nap like clockwork, while mine fights sleep like her 3-year-old life depends on it? Am I doing my little one harm by not forcing her to rest?

According to new University of Maryland research, parents can worry less about age-determined nap schedules, because little ones’ need for downtime depends more on how their brain works.

A paper published this week in a special sleep issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by Tracy Riggins, an associate professor in UMD’s Department of Psychology, and Rebecca Spencer, a psychology professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, shows that when children stop taking naps, it may be because their brain has become more efficient at downloading and consolidating what they’re learning. Classmates who haven’t taken that neurological step yet, however, may require more daytime rest stops.

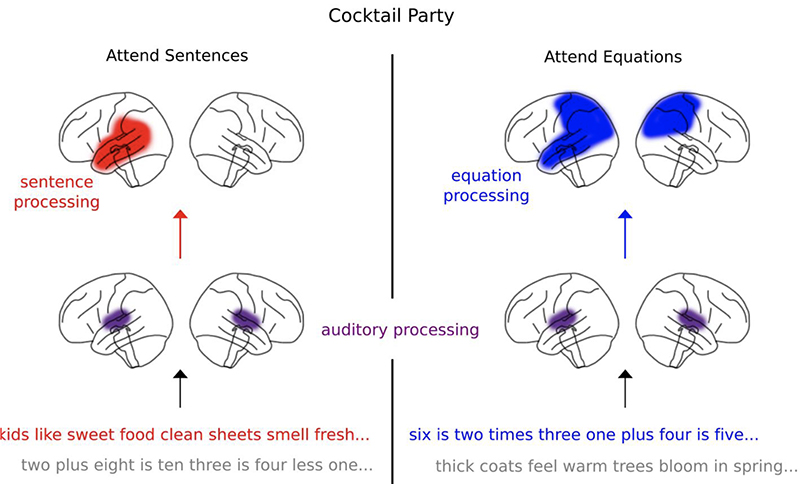

“If you think of the hippocampus [the part of the brain largely responsible for learning and memory] as a bucket, you know how much pressure there is for a child to sleep based on how full their bucket is,” Riggins said. “When the brain matures, it can either hold more, empty itself more quickly, or both, and that’s when a child may begin to transition out of napping.”

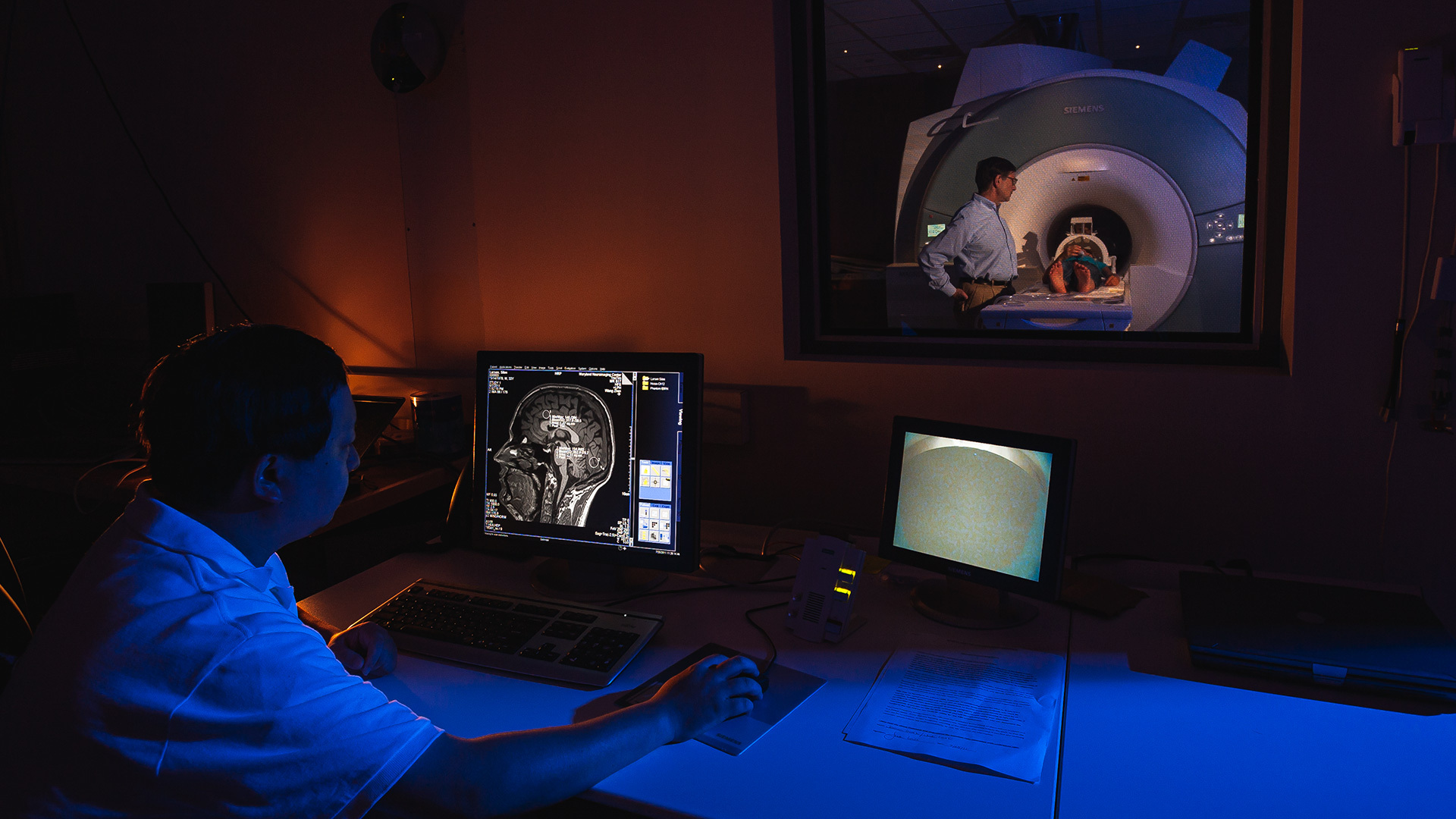

The researchers’ hypothesis was born out of previous research findings from Riggins, an expert on child brain development and memory, and Spencer, an expert on cognition and sleep. In an earlier study that was likewise supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, they assessed 200 4- to 8-year-olds’ ability to remember facts for a week while parents tracked their sleep patterns—ultimately finding that more sleep meant better recall. The researchers also found that hippocampus volumes of children who were habitual nappers were significantly larger than those who had transitioned out of naps, even though the children were the same age.

"Collectively, we provide support for a relation between nap transitions and underlying memory and brain development,” Spencer said. “We're saying this is a critical time of development in the brain, and sleep has something to do with it."

Riggins added that these findings raise an interesting question about how naps are, or are not, structured into children’s school days. Preschool napping procedures vary widely, while Maryland’s statewide full-day kindergarten has no built-in naptime.

Another question Riggins plans to explore in further work is the role of overnight sleep in preschoolers’ nap transitions, as well as the sleep and brain changes that occur in even younger children, like infants who have multiple sleep bouts per day.

While skipping a nap won’t do adults any harm, its benefits extend to them as well, she said.

“A nap is good for everyone; it helps consolidate learning even in adults,” Riggins said. “I always stress to students in my courses that if they are thinking about pulling an ‘all-nighter’ to cram or study, they should think twice.”

—Original story by Rachael Grahame in Maryland Today

Published October 26, 2022