News Story

Research Finds that Exercise Can Change Brain Structure in Healthy Older Adults

Every three seconds, someone in the world develops dementia. With a growing aging population, the number of dementia cases is expected to triple by 2050. Because there’s no cure, researchers like fourth year PhD student Daniel Callow are focusing their efforts on prevention measures.

A new paper from Kinesiology Professor Carson Smith's research team, of which Callow is a member, suggests that a single session of exercise can alter the microstructure and tissue composition of the hippocampus.

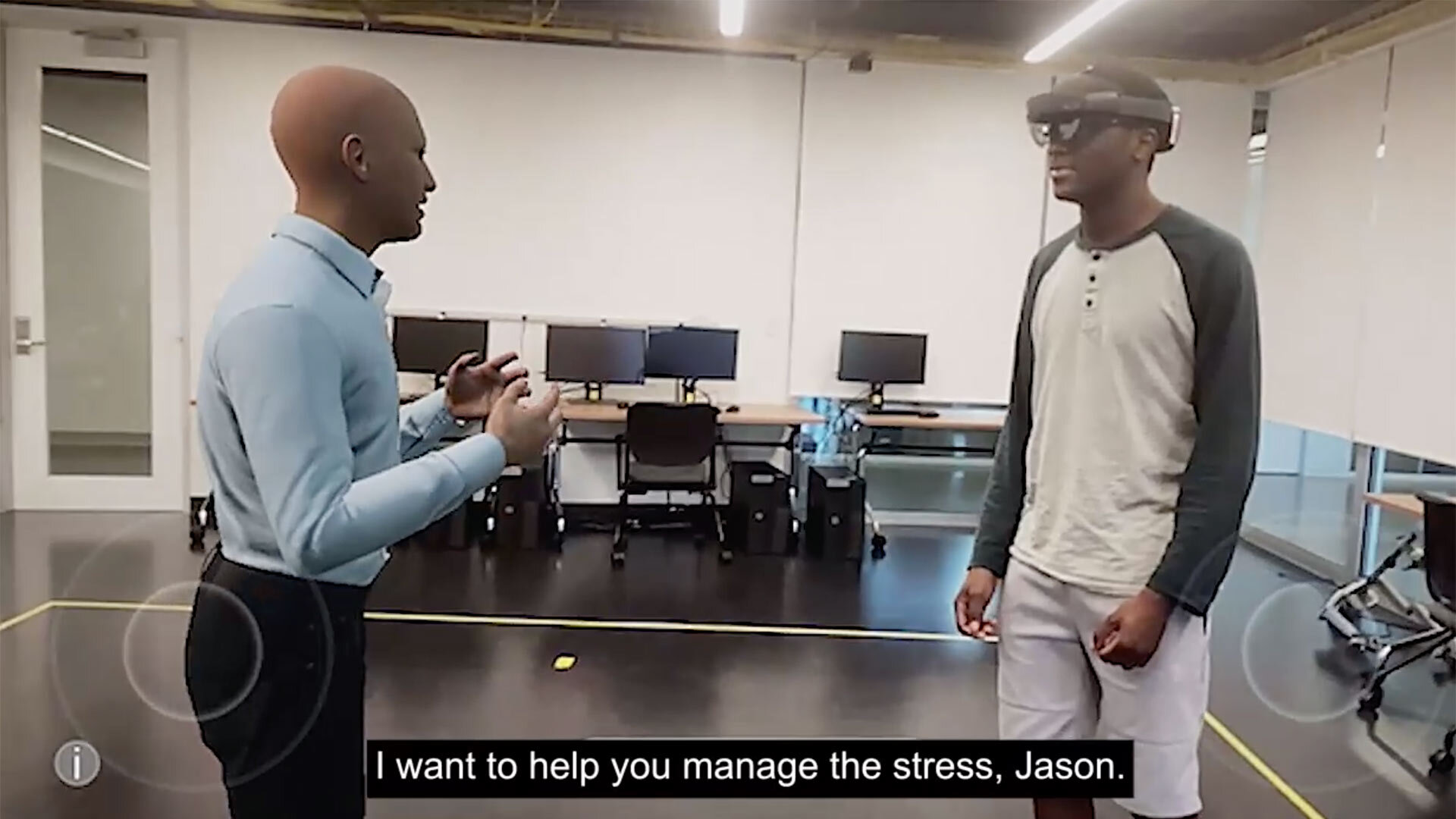

Along with Alisa Morss Clyne, associate professor of bioengineering, and Ganesh Sriram, assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, Smith is the recipient of a 2020 Brain and Behavior Institute seed grant. "Sex differences in exercise effects on brain microvascular endothelial glucose metabolism" looks to design more effective exercise training for those at risk of Alzheimer’s disease by identifying a biomarker for early detection—namely, brain glucose uptake.

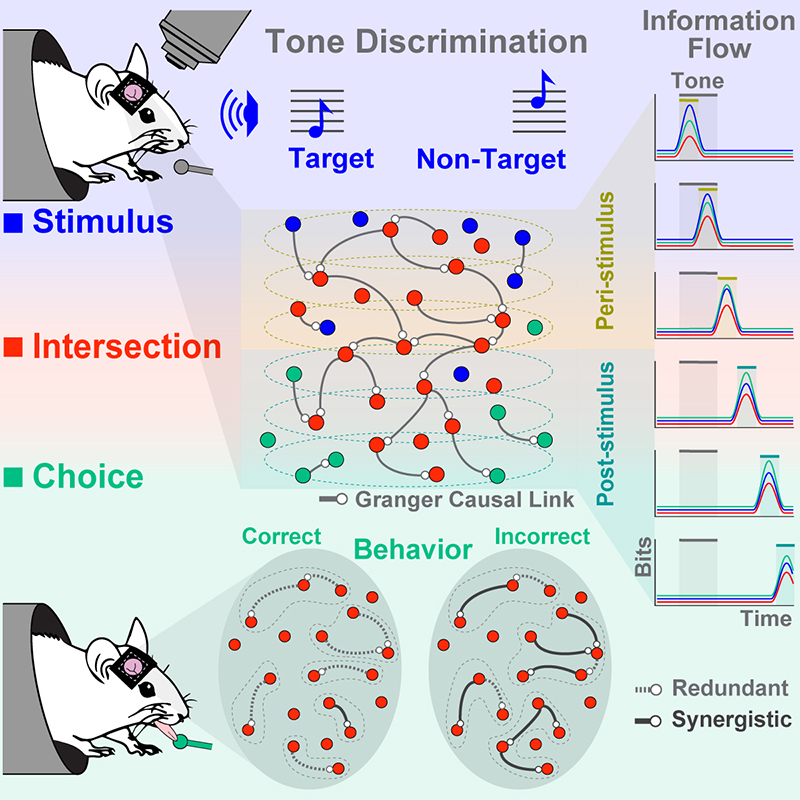

Callow’s research focused on measuring diffusion—that is, the movement of water molecules—in the gray matter of the brain. In the past, diffusion imaging has been primarily used in the white matter.

“You can think of the gray matter regions as if they're the city centers, while the white matter tracts are like a highway system,” Callow said. “For efficient cognitive performance, you want good communication between those important gray matter regions and intact good highways that don't have a bunch of potholes and stuff.”

Though similar research on animals exists, this study, “Microstructural Plasticity in the Hippocampus of Healthy Older Adults after Acute Exercise,” marks the first time anyone has looked at tissue microstructure following a single session of exercise in humans.

“What we found was that there was an increase in diffusion—an increase in the movement of water molecules—within that hippocampal region following the exercise compared to following the rest session in those healthy older adults,” Callow said.

The study is a continuation of research led by Smith that began when Callow was an undergraduate student.

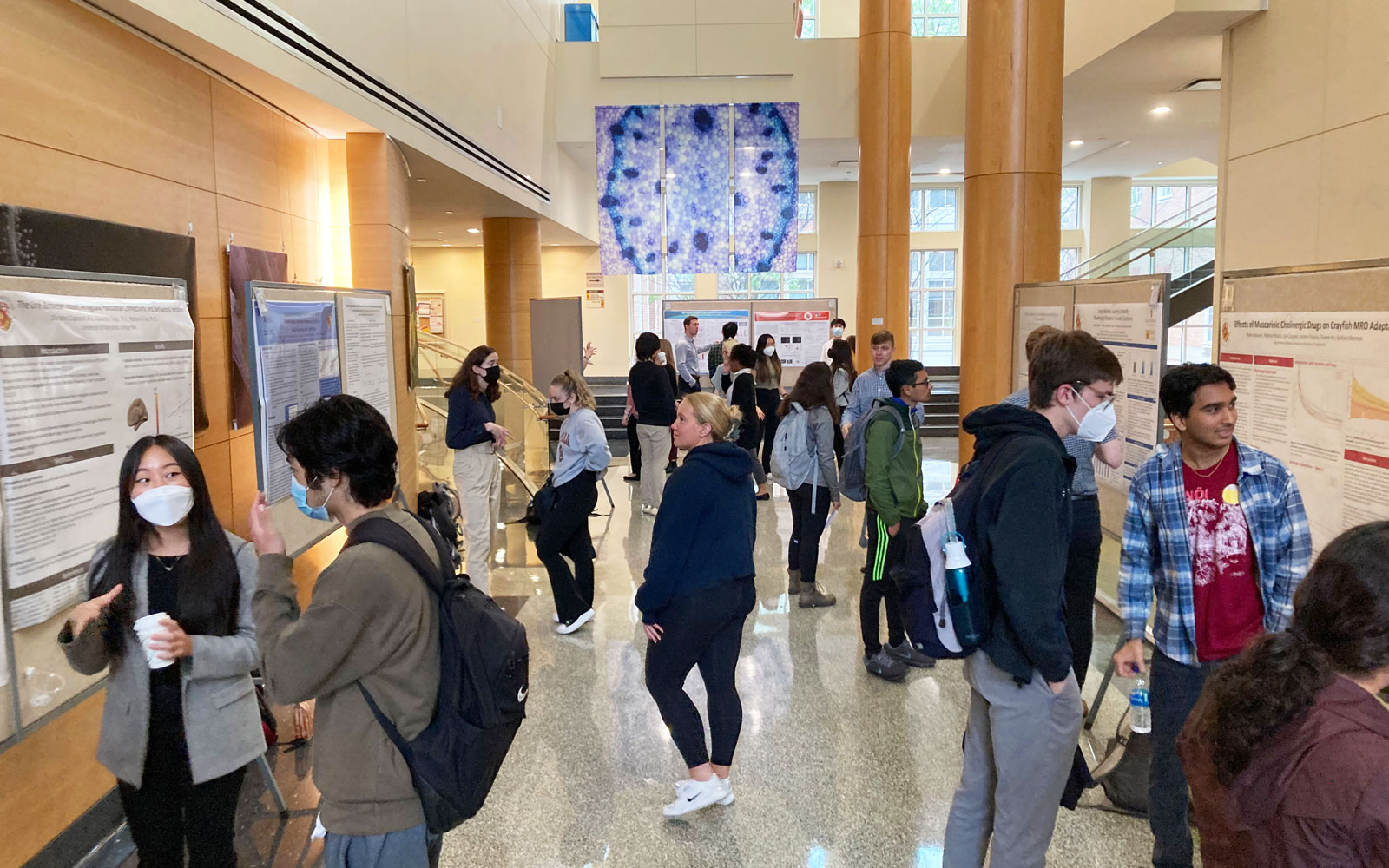

“We had healthy older adults [ages 55-85] come into the lab. On one of the days, they would do 30 minutes of exercise, and one of the days they would do 30 minutes of seated rest at the Maryland Neuroimaging Center,” Callow said. “Immediately after both of those conditions, they would then go into the MRI scanner and they would do a whole bunch of different MRI scans.”

Callow has become something of a resident diffusion expert at the University of Maryland: no one in the lab or on campus had been doing a lot with diffusion imaging. Previous studies have focused on the impacts of exercise on the size of the hippocampus, which shrinks with age.

“You can think of an imaging scan as getting a Rubik’s cube of the brain, where you get these voxels: individual little blocks, “ he said. “In a structural scan, you're just looking at how many blocks make up the hippocampus... But what we’re doing with the diffusion imaging is looking at what’s going on within that specific voxel, what’s happening to its tissue, as opposed to how big is the structure itself.”

Exercise has been shown to counteract some of the negative effects of aging, and it could potentially help people preserve their memory. But, Callow says, “there hasn’t been a lot of work done in humans to determine how a single session of exercise might be able to modify the hippocampus.”

Because this study used data collected a few years ago, it’s not totally clear if this increased diffusion in the hippocampus correlates with improved memory capabilities, though based on existing research, Callow suspects it does.

“For my final dissertation project, we are going to be looking at diffusion within the hippocampal subfields with really high resolution imaging, and we're going to use a very hippocampal-specific cognitive task in that study design,” he said. “We are looking at that as a next step.”

What this research does provide, he said, is hope.

“I think part of what’s exciting is the technique being able to be used in the future as a biomarker for microstructural changes and changes in tissue composition,” he said. “But it’s also interesting and exciting to see that even a single session of exercise may be providing some functional and cognitive benefit. Even going out and exercising for 20 or so minutes can really do something for you and potentially make a difference.”

Original story from the University of Maryland School of Public Health

Published October 1, 2021